From anachoretism to congregational monasticism

A brief overview of the historical development of monasticism

Ι. The sources

Monasticism is an aspect of Byzantine life for which we have a great deal of evidence. The main sources of study are the Life of Anthony written by M. Athanasius, the Greek Life of Pachomius written by the monk Tevennisiotis, the Lausiac History by Palladius, the Limon by John Moschos, the Philothean History by Theodoritus Cyrus, the Historia Monachorum in Aegypto by Rufinus, the Latin translation of the Canon of Pachomius by Hieronymus, the Ecclesiastical History of Sozomenos, the Ecclesiastical History of Eugrius, the Terms by Breadth and Title of Basil the Great, the Apostles of the Fathers and hundreds of biographies of monastic saints. We even have rules, disciplinary regulations, imperial decrees, meditations, letters, sermons, exhortations and apologies concerning monastic status.

II. Social and spiritual causes of anachoretism

Until the end of the second century AD, the sources of power and divine authority for the Christian Church were the prophets, bishops, martyrs and confessors. In the third century, when the Roman Empire was being swept by a Hellenistic ascetic trend of renunciation of the world, originating mainly in the Eastern provinces, a new source of power and transcendent perfection appeared: the hermit or retreatant. The concept of the “anchorite” originally had a political significance and characterised the tendency of certain wealthy Roman citizens to distance themselves from the political centres and live with their families in the countryside, thus expressing their aversion to the politics practised after the end of the Republic in Rome. After 250 AD, the concept of spiritual retreat was expressed mainly by monks, who, although living far from society, were very influential.

Gibbon attributes the emergence of monasticism to the decline of the Greek civilisation. Rostovtzeff attributes it to the dissolution of the religious ideas of the enlightened minority in the cities and the filling of the void by the primitive majority of provincials.[i] Other factors are also cited as reasons for many departures. The monastery offered security and refuge from the various problems of daily life and other obligations, such as taxes, the debts of poor peasants and military service. Some found a kind of camaraderie and relative material security in the communes. Officials and even emperors often had recourse to monasteries, willingly or unwillingly, after being dethroned or overthrown. For many, monasticism was the start of a future career as a bishop and, for others with little education, a means of social advancement. For others, it was a means of ensuring the salvation of their souls after death, but after having lived a rich secular life. Among them were aristocrats who converted their estates into monasteries and called themselves abbots, while the monks formed a sort of retinue. The “retreat” was in a way a rebuke to the increasing secularisation of the Church and its ministers. Some may have turned to the deserts for psychological reasons, a kind of anxiety that often makes people turn to strange historical phenomena, such as the hippies or youth political movements of the 1960s and 1970s. [ii]

οPeter Brown argues about the advent of an extraordinary historical factor in the religious life of Late Antiquity in the third century AD, which he describes as a genuine historical revolution.[iii] This was a new wave of religiosity that emerged in the Antonine period, which consisted in shifting the religious centre of life from public worship to the individual inner space of each believer, whether pagan or Christian. A new personal relationship between man and the divine was now required. Pagans became personally attached to a deity, such as Asclepius or Hermes Trismegistus, and could live alone with their god. This individual religiosity was also offered by Christianity. The ” Divine Man’’ of Late Antiquity, whose appearance coincided with the erosion of the classical institutional religious support, had a power similar to that of the monk, says Brown.[iv] « The Divine Man» took it upon himself to ensure that God met people’s everyday needs and relieved their distress. The search for ‘sacredness’ and ‘holiness’ in late antiquity led many people into the desert in search of ‘apathy’ and ‘tranquillity’.

The defining elements of a hermit’s life are the central place occupied by God’s judgement after death, the struggle against demons and the long hours of prayer. Leaving behind society and the problems of life, the hermit must face others, himself and the devil. But in overcoming them, he eventually falls into “apathy”, becoming himself a source of divine grace and authority. After years of living in the desert, in tombs and caves, the hermit lives in a world of visions and miracles. He appears as a new hero of the faith, superior even to the martyrs, an extraordinary intermediary between the transcendent world and the sensible world. Just what Late Antiquity needed to make the transition from the ancient world to the Middle Ages.

III. Hermetic and communitarian monasticism

The father of monasticism was Anthony, who began practising it around 270. At that time, there were still no monasteries. Antony isolated himself first in a tomb and then in the desert, not because he was economically deprived, like some of the “retreatants” of the 1600s, but because he followed the evangelical precepts on perfection and the absence of property. In the Life of Anthony, in which Athanasius’ monastic ideals are expressed, he presents a new hero of the Christian faith, a model for Christians to imitate. After a long period of practice, at the age of 55, Antony presented himself as a teacher and holder of the knowledge of asceticism, a remarkable career for someone who had received no education and who was not a Church official. He died in 356 at the age of 105. A few years after Antony‘s “departure”, the desert was filled with hermits who attracted disciples eager to lead the same life.

The desert gave rise to the need to tackle the problems of survival. The need for some form of organisation was quickly felt. The monks brought to the desert the habits of the Roman village and the work associated with it, such as basketry and pottery. It was in the desert of Nitria, for example, where, according to Palladio, five thousand retreatants had gathered, that they organised and created for the first time what is known as the diaconia and common worship assemblies. This form of monastic life is known as Lavra and is an intermediary form between eremitism and religious community. It was practised mainly in Palestine and other Byzantine provinces after the Arab conquest of Palestine, always in the mountains and not in towns. A Palestinian lavra consisted of a central nucleus with a church, refectory, shops, bakery, perhaps a stable and cells scattered throughout the desert. The hermits lived alone in their cells and attended vespers every Sabbath and mass every Sunday in the centre. There was a rudimentary “stabilitas loci”, unlike the groups of retreatants who often changed their place of residence. The members of these groups lived in close contact with each other, gathered around their spiritual father. The disciples were generally young monks who wished to learn the ascetic art. The group had no possessions and its members survived either through their work or through almsgiving, or even through help from neighbouring communities.[v]

The first to shape the community system was a genius of a tailor, Pachomius. As Palladius tells us, he became involved in this work following a divine revelation.[vi] He was born at the beginning of the 3rd century in Upper Egypt to pagan parents of modest social status. He served in the army under Constantine the Great, where he is said to have come into contact with Christianity while wounded and in captivity. Once released, he was baptised and lived as a hermit. He established his first monastic community at Tavennissos and wrote a canon, the main element of which is obedience. He died in 346.

The constituent elements of the commune are a common place of residence, the organisation of a common economic life and the existence of a central authority. In the Pahomian organisation, the monks wore similar clothes, ate the same food at fixed times, had an identified task inside the fortified monastery or in the fields, had common and fixed prayer times, and had a common divine service on Saturdays and Sundays. This monastic way of life was considered by the Fathers to be the best and surest path to perfection. In the commune, the monks have everything in common, worship being celebrated in the monastery’s Catholicon , which is also the centre of the building. But the most important thing is obedience to the prelate. All sorts of people have flocked to these communities for the most diverse of reasons. Alongside good and dedicated monks, there were also tax evaders and people in trouble with the law.

The great stars of monasticism worked mainly in Syria. The monks there lived in mountainous areas, often praying and chanting day and night, and had a particularly notable influence on the country’s social structures.[vii] In addition to a type of monasticism similar to that of Egypt, another type of monasticism emerged in Syria, characterised by spiritual extremes and marked individualism. Ephraim the Syrian describes with admiration the “shepherds”, a class of monks who fed only on the grass of the earth. Theodoret of Cyrus describes the life of Simeon who, after distributing his goods to the poor, settled in the monastery of Teleda. There he indulged in extreme forms of asceticism, such as standing on a tree and keeping vigil while praying, shutting himself away in cavernous places, tying himself up with chains, until he finally built a pillar on which he stood. He lived 37 years in this way and was canonised after his death.

In addition to the stylists, other extreme forms of asceticism in Syria and Mesopotamia – the “homeless”, the “silent” and the “vigilant” – were also present. But the most extreme form of monasticism to appear in the region of Asia Minor, Syria and Mesopotamia was that of the Messalians of the 4thου century, who prayed, sang and danced incessantly and did not work, but begged for their food.

If the commune were created and nourished by Eremitism, it would, in turn, become the main source of nourishment for Eremitism. In the commune, the monk would receive the necessary spiritual education and basic spiritual supplies to enable him to face the desert without the danger of the delusion that runs those who, uncritically, begin their struggle in the desert without a simple spiritual guide at their side.[viii] The most ardent defender of the community ideal was Basil the Great, who reconciled monasticism with the cities.[ix]

The commune was the main type of female monasticism, although there were also female ascetics such as Marana, Kyra and Domnina, mentioned by Theodoretes Kyrou. Widows often retired to monasteries, and several emperors’ wives deliberately ended their lives in monastic garb, such as Procopia, wife of Michael I Ragabe, Theophano, wife of Leo VI, Sophia, of Christopher Lecapenos, Theophano, of Romanos II, Catherine, of Isaac I Komnenos and Irene, of Manuel II Palaiologos. Others are mentioned who were locked up in monasteries against their will with their daughters and sons.

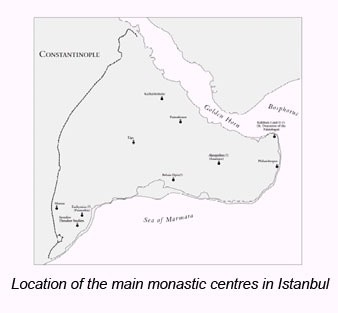

Monasticism came to Constantinople from Syria. The first monastery was founded in 382, and monastic life flourished in the fifth and sixth centuries with the support of the aristocracy and a series of emperors. The oldest monastic centre dates from this period, founded by Justinian, the monastery of Saint Catherine of Sinai, which boasts an extensive library.

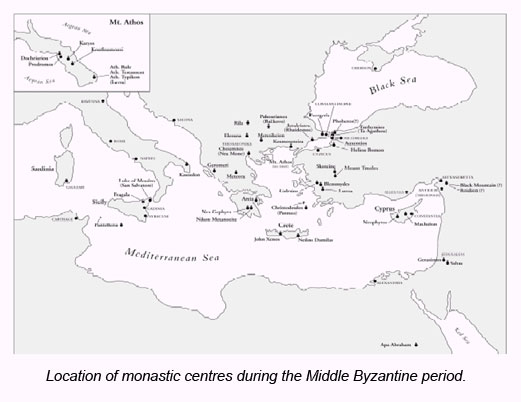

In the seventh century, Orthodox monasticism extended from Palestine to Mount Sinai and Alexandria, to Cilicia, Cyprus and other islands, although it declined considerably as a result of the Monophysite schism. But “the heroic age of monasticism was over”.[x] In the 8th century , during iconoclasm, monks were prosecuted because they were seen as defenders of the tradition, i.e. of iconoclasm. After the Seventh Ecumenical Council, monasticism enjoyed a new lease of life with the reconstruction of numerous monasteries. In the 9th century, monks once again became the main focus of resistance to the second period of iconoclasm. An important monastic figure of this period was Theodore Stouditis who, with ideals similar to those of Pachomius, created a “federation” of monasteries and a book-copying workshop in the monastery of Stoudios. The founding of monasteries continued unabated throughout the 9th and 10th centuries. During this period, numerous legislative texts were drawn up to regulate issues relating to monasticism and, in particular, monastic property.[xi] Under Basil II, monasteries were granted to be run by lay people, the “charisticarii”. The accumulation of wealth and luxury in many monasteries was often scandalous. The best surviving examples of Byzantine architecture and painting, such as Hosios Loukas, the New Monastery of Chios and Dafni, are Catholica from the Middle Byzantine period.

In the 10th century, Athanasius founded the first large, compact monastic centre on Athos, which was to acquire great religious, economic and political power. Athos soon became a “holy mountain”, i.e. one that was conducive to the practice of hermeticism and monastic tranquillity, which led to a steady increase in the number of monks.[xii] At the end of the 13th century (ου ), the monastic self-government was established with a common administration and worship on Sundays and public holidays. Food was a private matter and was not particularly ascetic.

In the centuries that followed, monasticism was nothing more than a social institution, and life in monasteries was another form of conformism. Some remarkable personalities tried to recall the essence of the spiritual life, like Simeon the New Theologian, or to criticise the evils of monasticism, like Eustace of Thessalonica. The intense need for a new esotericism was expressed mainly in the 14th century by the hermits of Mount Athos. For the leading exponent of this movement, Gregory Palamas, monks were people with spiritual vision, like the prophets of the Old Testament. They were able to bridge the gap between the transcendent and the terrestrial through prayer and breathing, and to see the “uncreated light”. Despite the polemics that Hesychasm encountered, Gregory Palamas was declared a saint and monasticism won a great victory with the recognition of Hesychasm.

IV. Monasticism in the West

The West came to monasticism with a certain delay, and the first monasteries were built in the 5th century. Initially, Western monasticism had no particular differences from Eastern monasticism, since it was also inspired by the common Mediterranean tradition. At the end of the 5th century, Saint Benedict organised the movement of congregations in a practical spirit. The Benedictines took on the task of assimilating the new peoples. The monks became explorers, farmers, breeders, copyists, preachers and missionaries.

The differences began to emerge as the map of the old Roman Empire changed with the emergence, beyond the Alps, of new European states (Franks, Celts, Germans) and of Islam in the south. The invasion of new peoples in Europe created new nations with their own religious and cultural traditions, while Rome tried to assimilate all this amalgam into the funnel of Christian society. Peter Brown notes that religion in the West “breathed through the chaotic gaps in the structure of society” while “the Byzantines were able to adhere to the ‘sacred’ where they needed it”. [xiii]

This general upheaval created the spiritual conditions necessary for the development of a new asceticism, that of the monastic orders, such as the Franciscans, Dominicans and Jesuits. All these orders introduced something new into the spirituality of Christian monasticism, missionary work and the evangelisation of peoples, with the aim of cultivating the peoples who had just converted to Christianity. In most Western monasteries, there was a common standard and a confluence of values[xiv] , because the cultural and social work that monks were called upon to carry out had specific requirements. Western monks were generally well versed in the humanities and could engage in similar studies. In the East, monks generally did not have such a high level of education, although some spent their breaks studying or copying codes. [xv]

In Byzantium, there was never a single monastic organisation imposing rules, duties and commitments to a certain way of life. In the West, on the other hand, monasticism put itself at the service of the Church and the world, responding to the ideals and needs of the new states and major urban centres.

Conclusions

Byzantine monasticism is a spiritual movement that arose in the crumbling years of Late Antiquity and survived the Byzantine Empire in the midst of intense contradictions. It clung to the ideals of hermeticism, a disregard for everyday life, and an interest in the afterlife, thus responding to the ideals and needs of a society that was as contradictory as the Byzantine society.

Georgia Papadopoulou is a certified tour guide. She holds a degree in Greek cultural studies, a diploma in museum education, a master’s degree in cultural policy, management, and communication, and an MEd in adult education.

| Bibliography |

|---|

| Efthymiadis, S. and others, Public and Private Life in Greece I: From Antiquity to the Post-Byzantine Period, volume B, Public and Private Life in the Byzantine and Post-Byzantine World, Patras, 2001. |

| Papachrisanthou, D., Le monachisme athonite. Principes et organisation, Athens 1992 |

| Beck, H. G., The Byzantine Millennium, ed. D. Kurtovik, Athens 2000 |

| Brown, P., The world of late antiquity 150-750 AD, ed. Stamboulis E., Athens 1998 |

| Mango, C., Byzantium, the empire of the new Rome, ed. Tsougarakis D., Athens 2002. |

| Brown, P., Society and the Holy in Late Antiquity, California 1989 |

| Brown, P., The World of Late Antiquity, N. York, 1989 |

| Dodds, E. R., Pagan and Christian in an Age of Anxiety: Some Aspects of Religious Experience from Marcus Aurelius to Constantine, Cambridge 1965. |

| Rostovtzeff, M., Histoire sociale et économique de l’Empire romain, Oxford 1926 |

[i] Rostovtzeff, Oxford 1926, p. 58

[ii] Dodds, Cambridge 1965, p. 254

[iii] Brown, N. York 1989, pp. 49-112

[iv] Brown, California 1989, pp. 103-152

[v] Papachrysanthou, 1992, pp. 71-72

[vi] As he was sitting in the cave, an angel of the Lord came to him and said, “Go, you have come this far, and sit down in this cave. “Go, you have come this far, and sit down in this cave. When he comes out, gather together all the young men, and dwell with them; you shall rule them in the way I have shown you.”

[vii] Brown, California 1989, 103-152

[viii]The 41st canon of the Holy Synod of Trullo stipulates that as a condition of departure for the desert, the monk must remain in a commune for at least three years.

[ix] Efthymiadis, 2001, p. 214

[x] Mango, 2002, p. 138

[xi] Relevant laws of Romanos I Lecapenos (935), Constantine VII (947) and Nikiforos Fokas (964).

[xii] Papachrysanthou, 1992, p. 99

[xiii] Brown, California 1989, pp. 194-195

[xiv] Beck, Athens 2000, p. 302

[xv] Beck, Athens 2000, p. 301

Leave a Reply