Ion Siotis, May 2018

The presence of an extensive system of trenches (in French “entailles”) dug along the coast line of Paros and Antiparos has been noted since the middle of the 19th century. The fact that, in most cases, the trenches are submerged to a present depth approaching 2 meters gives valuable information on the changes in sea level since their construction, if only they could be dated. Conversely, if one had reliable information on such sea level changes as a function of time, it might be possible to date their construction and, possibly, provide some insight on their function.

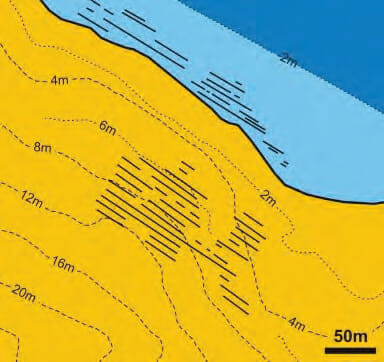

Systems of trenches have been identified in various locations around Paros such as the bay of Naoussa, Santa Maria, Drios and Voutakos. In general, they run parallel to the present coast line but in some cases they appear at an angle, however, coast line changes over time introduce uncertainties as to the original angle of the trenches to the coast line.

The scale of the systems of trenches, in most cases at least 5-6 parallel trenches, each over 200 m in length, ~1 m wide and up to 30 cm deep, implies a considerable investment in labour and this has led to a variety of theories as to their function.

The archaeologist O. Rubensohn, in 1901, follows the original hypothesis of Commander Graves who first, in 1842, suggested that they served as salt-pans (salines). Half a century later I. Morrison, in the context of the archaeological research at Saliagos, a small island between Paros and Antiparos, assigns a function of a “Hellenistic field-system of vine trenches”. This interpretation has been taken up by several other authors who invoke the existence of a local Dionysus cult. In addition to these two interpretations the systems of trenches have been assigned a function related to naval slip sheds, to slips connected with the transport of marble blocks or to the remnants from building block quarrying activities. Each one of these interpretations has been criticized in the scientific literature and, in order to reach a coherent interpretation, some authors abandon the notion of a unique function and propose a multitude of functions depending on local details.

In this brief account we want to point to a feature displayed by the systems of trenches around Antiparos and Despotiko which may throw some light on the issue of their function.

There are at least three such systems, all shown in fig 1, 2 and 3 show details of the Glyfa system whereas figs. 4 and 5 show the corresponding features of the Despotiko system. Finally, fig. 6 shows processed satellite photo of the Despotiko trenches. For both the Glyfa and Despotiko trenches the bottom layer is practically intact and does not display holes at regular intervals as would be expected if their purpose was related to vine culture. In any case due to the vicinity to the sea the root system would be adversely affected by sea water. It is also unlikely that the considerable labour required to carve the trenches in the calcrete would be justified since there is plenty of land available at a short distance from the coast line. Another common feature of the Glyfa and Despotiko systems is that at the end point of the trenches a basin, circular at Glyfa and rectangular at Despotiko, has been carved out in the calcrete. Such a feature would not be necessary for vine cultivation.

For further information, email: siotis@inp.demokritos.gr

An interesting feature of the Despotiko, Remmatonisi and possibly Glyfa tenches is that there are signs for the continuation of the trench system in the adjoining land. This was pointed out for Despotiko in 2009 by E. Draganits, shown in fig. 6, in the context of a geological survey of the area related to the excavations at the Apollo sanctuary. For Remmatonisi this was confirmed recently by the earthworks for a new building and swimming pool in that location.

Assuming that the number of land based parallel trenches in Despotiko, as suggested by Draganits, is at least 12 and that the trenches presently visible underwater number at least 7 one is dealing with a system of about 20 trenches, each at least 100 m long leading to a total length of 2 km. These observations, combined with the corresponding data from Remmatonisi, suggest a major human activity which is worth exploring further. As Draganits points out “… future studies on the trenches should carefully consider the particular relative sea level during the time of their creation and use to clarify, if specific furrows originally have been intended for sub-aquatic (aquaculture), peri-tidal (boat slip ways, ship sheds, salt evaporation) or terrestrial (agriculture) purposes…”.

One way to explore these issues is to look for salt traces on the walls of the land-based trenches. If such traces are found the aquatic hypotheses would be strengthened, if not one would have to explore further the agricultural interpretations.

Fortunately, present day analytical techniques, some developed at the National Center for Scientific Research “Demokritos”, allow such determinations provided that, in order to obtain reliable results, the soil sampling is done under carefully controlled conditions. We hope that the archaeologists responsible for Despotiko (Y. Kourayos) and Antiparos (Z. Papadopoulou) will initiate such studies in the near future.

Leave a Reply