Dear friends of Peter

Sorry – it took some time to write this.

Above all, because we could not fully believe it. And still do not really understand it. Peter was much too alive to die.

But he did – at least as alive as possible. He died on April 23, 2021, clear-headed, aware of his situation, without complaint at three o’clock in the morning at the Health Center in Paros.

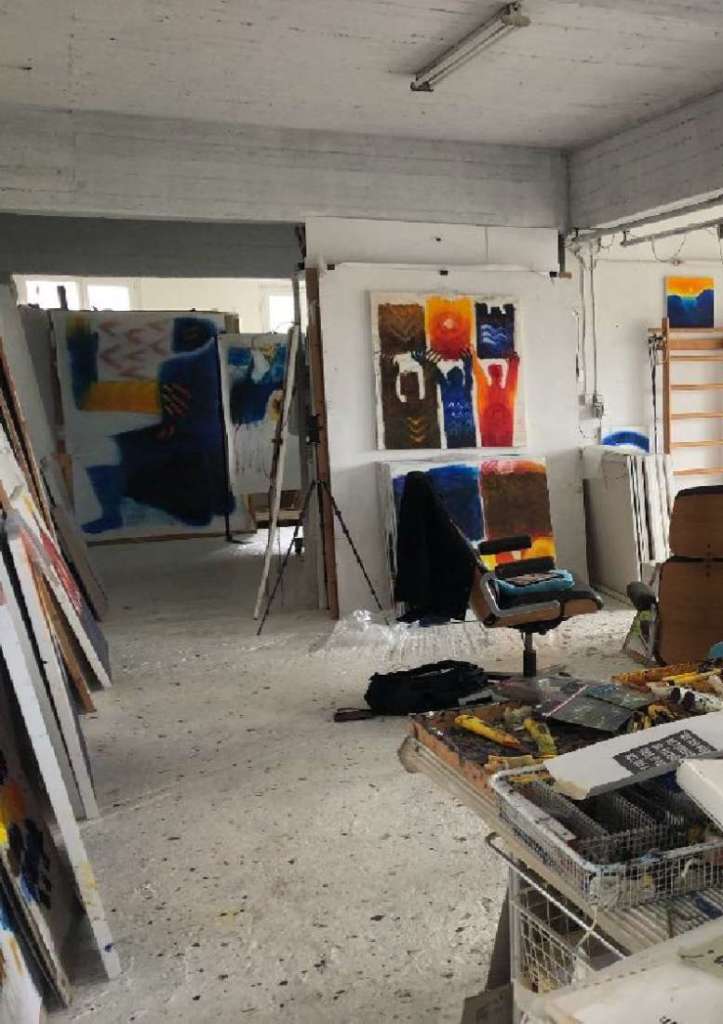

And, as always, he was in the middle of work. You could say: the only thing unfitting about his death was that he died.

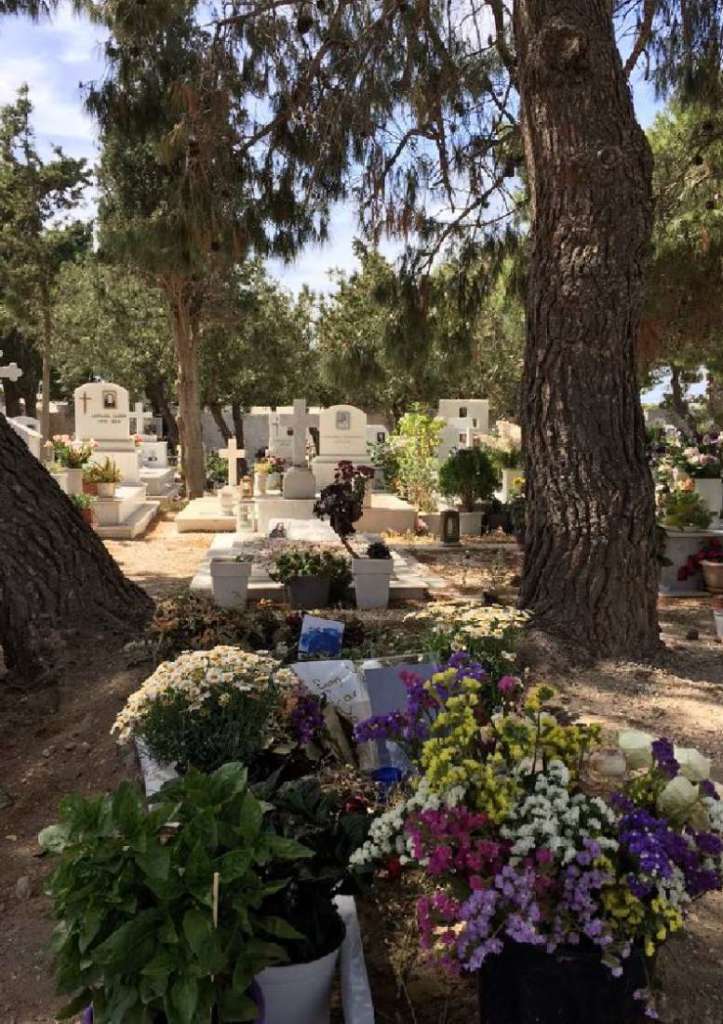

The funeral took place five days later in the small cemetery in Paros. Because of Corona, only nine people were allowed. A few more came, the sun was shining and the south wind was blowing.

It is a really beautiful cemetery, with white marble graves, photographs of the deceased, a tiny chapel and enchanted by the scent of the flowers and many pine trees.

Peter’s grave is in the best place, the only one between two trees.

So far the most important. Below are some photos plus Constantin’s speech he held at Peter’s grave – he wrote it down from memory as best he could.

And: Peter has not yet fallen silent. He continued to paint until the end. We’ll report back with more on this on June 3 – 40 days after his death.

Heartfelt thanks to all of you who wrote faster than we did. We have received incredibly beautiful, heartfelt condolence emails.

We haven’t been able to answer all of them yet. But we will. Your words have touched our hearts. And comforted it. Thanks for that!

We are very happy about Peter’s life. And we miss him very much.

With love –

Heidi Seibt

Alexander Seibt

Constantin Seibt

PS: If you want to listen to something, here are three more of Peter’s favorite tunes – one by Bach, one by Hadjidakis and an all-time classic by Frank Sinatra.

PPS: If you miss Peter, check out his paintings, it helps a bit (we tried).

Peter

The advice my father gave me for all ambiguous situations was, “Go out there and fascinate them!”

Little in life has brought me more trouble – but almost always the kind of trouble that’s worth it: You make a promise, and well, now you have to keep it.

Today, with this speech at his coffin, I have little choice but to take his advice one more time. And to start talking, although I am still completely unclear about what.

Because really, I still can’t believe that Peter is supposed to be dead – I’ve been crying my eyes out for the last few days, but still, I wouldn‘t be surprised if he came around the corner after coffee tonight, grinning broadly and without explanation.

I had never thought he would die, ever. Okay – partly out of cowardice. But mostly because dying was so out of character for Peter. He was a timeless man – as timeless as I’ve ever seen anyone to be. He loved everything archaic: the sea, the landscape, the wind, the colours, the light, the raising of the hand. Everything around him was classical: the literature, the music, the quotes. Even unshaven, his face looked like the profile on a Roman coin.

If he came around the corner now, what would drive you crazy was that he would almost certainly provide zero explanation. But instead a lecture on the topic that death is overrated because only the present counts.

No wonder, as children, my brother and I were convinced that he worked as a spy. Peter was then, in the seventies, a man with a slim-cut suit, blue turtlenecks, black glasses, generous but surprisingly random gifts from the duty-free airport stores, and the smell of a tobacco pipe. A very typical, very pleasant smell that, to our amazement, did not disappear once he stopped smoking.

Once a year, when I had to state at school what his profession was, my mother would say, “I don’t know either. Write ‘merchant’. Or, ‘import-export.'” It took me over 15 years to find out that he worked as a consultant for businesses.

He loved to talk about fundamentals, the arts, or the future – talking about the past was a waste of time. Almost all the stories from his life (two dozen anecdotes at most in 55 years) I heard only one single time, and as if in passing. Only two of them I heard more than once. The first was:

“I was nine years old when my mother called me downstairs and said,

‘Peter, dress warmly; we’re going for a walk.’ I looked at the wardrobe and knew: You’ll never see any of this again.”

Outside, the snow was piling up. Peter’s youngest sister lay in the stroller, the family’s photo albums under her pad. They caught the second-to-last train out of Breslau – the passengers on the last one died a little later in a bombing raid.

At age 9, the child who would become my father was history. Who or what replaced him remains unclear. I heard only a few things from him: that one had to throw oneself into the ditch when low-flying planes attacked with the machine-gun fire, the panic in a collapsed bunker, coal thefts from freight trains, cigarette counterfeiting in Bavaria, later hauling acid vats instead of school.

The other anecdote he told me twice was about a woman wading through the snow heavily laden in three fur coats, suddenly setting down her two suitcases, dropping the spare coats, walking away liberated through the snow and whistling.

That was his story, too: At the age of 14, he already had to help feed the family. He was in hospital for months with meningitis, had no job and no school-leaving qualifications when, at 25, he got his first real chance: a job in Rowenta’s advertising department – after which he never looked back. He made his career at a horrendous pace, got married, had two sons, moved to Switzerland – and thus put a national border between himself and the past.

The impression I had of him as a child was that of a shot arrow – blurred but full of energy because of his impressive speed.

The man I knew best was one of the most enigmatic people to me: Something had shot him at that speed. What exactly? I never got more than a hunch.

He made money with ease in those days – and spent it with equal ease. We always had the latest prototypes of technical devices at home – I brought a calculator to school before the teachers even knew that calculators existed. It is true that most of the prototypes functioned rather erratically. But they were often bought in multiples. Later, during the house clearance, I found about six of the first electronic typewriters stacked in original packaging. Also, Peter bought four identical suits to solve the clothing problem in one fell swoop. Only he didn’t wear any of them because he never tried them on before buying them.

The only thing he stayed frugal with was our pocket money: We got the least of all our peers – and were thus introduced to the wisdom that freedom in real life would mean, above all, “low fixed costs.”

I thank him for that to this day – and for the fact that he himself didn’t adhere to that insight for a moment: When he started his own company, he rented an entire house with garden as an office. Basically, he didn’t care what he spent his money on. What interested him was not what was bought.

– but abundance, freedom and the pure act of generosity.

And that was the thing. As I later observed among my relatives, there were two reactions to flight, hunger and poverty: Some made very cautious careers, step by step, and saved where they could – today, they all have a paid-off mortgage and a small fortune.

The others went for bold coups. They often landed amazingly big fish – just to throw them back into the sea. When my mother would protest the spending, my father would reply that if you wanted to make money wisely, you had to keep the cash moving.

One of my earliest childhood experiences was walking down the stairs behind my father. Suddenly he stopped. I looked up, he looked down, grinned broadly and said, “You will inherit nothing.”

It’s what I’m most grateful to him for: He inherited nothing. Whatever hunger or guilt or fear there had been – he passed none of it on. His lesson to us two sons was: freedom from fear. And the conviction that if we did something with passion, someone eventually would pay money for it.

Being Peter’s son meant having an incredible edge over almost all of his colleagues in boldness, confidence, and blindness: Failure, embarrassment, dry spells were not a problem, because ultimately you couldn’t fail if you were doing what you loved. The only serious compass for one’s career was one’s heart.

And the only condition was not to want anything modest: Peter taught us that the real work was to reinvent your craft. And to think like a dream: big – and out of focus for as long as possible. Just as he showed us that when painting a landscape, you should squint your eyes a bit to see it sufficiently out of focus – because that’s how you saw the whole.

Being Peter’s son also meant inheriting his tradition to not have a tradition. Peter was – as my mother told me – the only person she ever saw reading encyclopedias from A to Z. He was the only person she ever saw reading encyclopedias. His office library was wide-ranging: ultra-hard crime novels, Japanese haikus, complete editions of classics – Plato, Shakespeare, Tucholsky – non-fiction books on everything from floriculture to outer space, the latest avant-garde novels, the Stoic philosophers, art books weighing dozens of pounds and several shelf meters of quotation dictionaries. As well as, last but not least, in a locked drawer a few issues of Playboy. And all the shelves in a for Peter typical “tidy mess”; with owls, notepads, office lamps and a human skull.

The notes in the margins proved that he had read just about everything. I read most of it, too. And learned, without him ever telling me, that you could choose your roots on a case-by-case basis. Even long after I was writing as a journalist, I would take a book off the shelf for style and attitude – usually something American, French, a classic, or something archaic like Kipling’s Jungle Book or the Bible.

Peter was a flawless self-made man. He was almost 50 years old when – also to his own surprise – he found a home. He came to Greece for vacations and loved everything – the light, the sun, the sea, the Greeks. Almost overnight he looked like a Greek himself: Once he fell asleep on the beach and found a few coins and a small banknote in his cap – passers-by had mistaken him for a local beggar.

During that vacation, he began to do systematically what he, up to this point, had done sporadically: paint. His first paintings, in Mykonos at that time, were fascinated by the colours and the port cities: the white of the cubic houses, the blue around the windows, the red of the domes on the churches that had the shape of a steam locomotive.

Soon he was spending not only the vacations but the whole summer on an island. He rented a house on Paros. And one day he moved completely: If you wanted to see him, you had to get on a plane.

The third thing it meant to be Peter’s son was loneliness. Because social rules counted for nothing and there was no instance in the world except his own compass.

He himself never seemed to feel it – besides painting, he valued nothing so much as independence. For many years I was convinced that with enough oil paint, canvases, espresso capsules, books, and a serviceable radio antenna, he would have lived on a desert island without further loss.

The damning thing about Peter was that he was as generous as one could wish. But only in giving. In taking, not at all. All my life I never knew what to give him, because he always had what he needed. And I never knew if he needed me. And if so, for what.

For a long time, I would have bet against Peter ever needing anyone. And against ever having a happy marriage. The marriage with my mother was such that before it ended no one suspected it was no good, but after it ended no one knew why it had ever been contracted.

His second marriage with Heidi went amazingly different: it seemed to me that from year to year it became more familiar, more equal. Closer. It was not for nothing that Peter painted Ulysses again and again, who finally arrives in Ithaca after war and years of wandering – he became more serene and calmer every day. One had the impression: the arrow was on target. The flight was over.

All the kinetic energy exploded into painting – he painted countless series of pictures – a universe of light. He was a master of abundance. He did it as relaxed as others breathe – and did it until his last day: sketched, painted, drank espresso and never looked back. And as for the future, he said, “To hell with the consequences.”

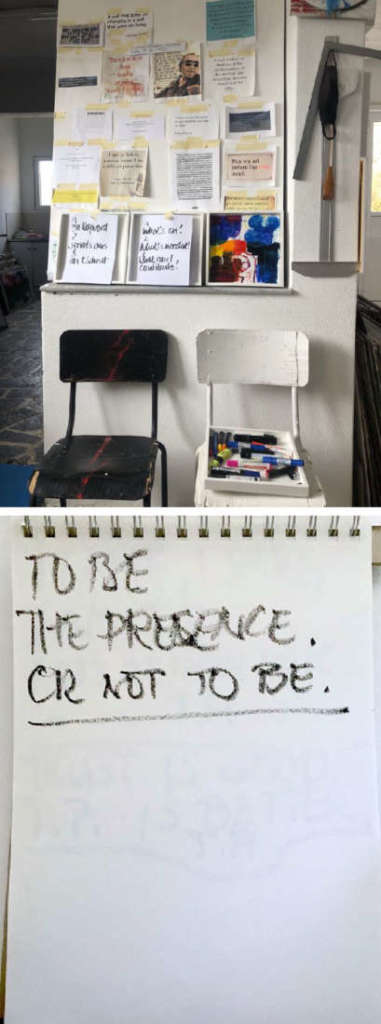

One of the last phrases he wrote down was:

“To be the presence. Or not to be.”

Dying really didn’t suit him, and he did so almost in passing, quickly, with a clear head and without further drama.

Goodbye, Peter. Be kissed, my father. Have a good trip, my boy. And if you should arrive somewhere: Go out there and fascinate them!

Constantin

Thank you, friends, that’s all – almost, anyway. But for the last words, we pass on to one of Peter’s favourite poets:

Wer sich als Quelle ergießt, den erkennt die Erkennung; und sie führt ihn entzückt durch das heiter Geschaffne, das mit Anfang oft schließt und mit Ende beginnt.

Who pours out as a well, the recognition recognizes;

and it leads him delightedly through the cheerfully created, which often closes with beginning and begins with end.

R. M. Rilke, Sonette an Orpheus

Leave a Reply